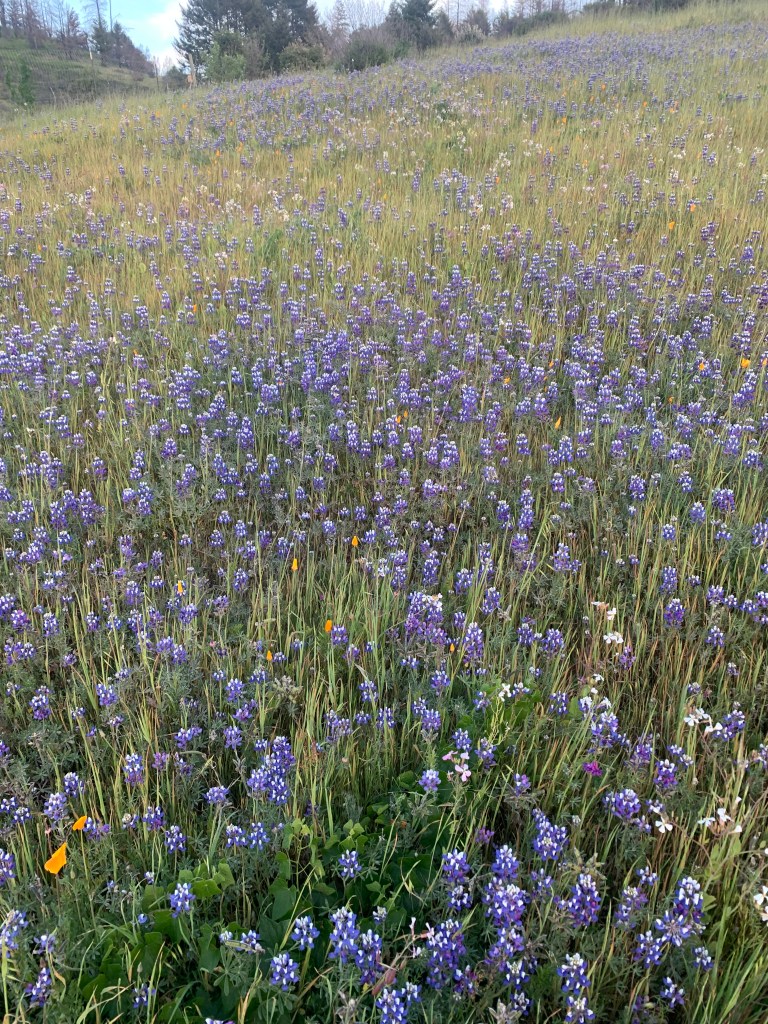

In the local prairies, it is an especially prolific lupine blossoming year. Do you have a favorite place to visit lupines? The most prolific, bright, large flowered annual lupine in our area is called sky lupine, because when it is in full bloom in large fields, it looks like someone turned the world upside down. The scent is heady- it smells purple. For those of us who grew up smelling purple in grape Kool Aid or various artificially flavored grape bubble gums, it makes sense that sky lupine smell purple. In good years, I am able to go to my favorite lupine patches at just the right time when acre upon acre are giving off that scent and making extensive mats of lupine colors.

Lupine Diversity

Lupines are pea family plants. Look carefully, and you’ll recognize that sweet pea shaped flower. Lupines typically have flowers in a spike of tightly packed whorls with older flowers turning to seed pods at the bottom and new flowers opening at the top. Lupine seed pods look like pea pods. Sky lupine pods explode on warm days pitching seeds far from the mother plant.

Sky lupine isn’t the only lupine around, there are many lupine species in Santa Cruz County. It might make a good treasure hunt to try to see them all. According to Dylan Neubauer’s Annotated Checklist of the Vascular Plants of Santa Cruz County, California (every naturalist in the County should have this), there are sixteen lupine species in our tiny county. Sky lupine is the only one to make a big show in the grasslands.

Who Eats Lupines?

Italians eat lupines! Strains of white lupine, Lupinus albus, have been cultivated for food throughout Europe. But you have to grow the right strain- some strains are very toxic! In fact, most lupines are toxic…

Here’s a challenge: find sky lupine leaves that are being eaten by a butterfly or moth caterpillar! In researching this essay, I explored the possibility that some beautiful butterfly larva fed on sky lupine. Nope! Lupines famously have some potent toxins. Some species of lupines poison cattle, though I’ve not heard that livestock owners are concerned about sky lupine around here. There are some butterflies and moths that feed on perennial lupine bushes locally, but none that we know of that feed on sky lupine.

Lupine Pollinators

It isn’t a burden to sit in a sky lupine patch to watch for pollinators. You’ll quickly realize that bumble bees love lupine flowers. And, if you look at those bumblebee legs, you’ll see the distinct yellow orange sky lupine pollen color – they collect big globs of it.

And yet, sky lupine doesn’t need a pollinator, it can self-pollinate. But sky lupine flowers make more seed if they get pollinated by bees. The species has an interesting adaptation- some tiny hairs that prevent self-pollination at first; these hairs wilt with time, allowing self-pollination if all else fails.

Planting Lupines

You might be tempted to plant sky lupine- certainly expensive wildflower mixes contain this species and display its color on the fancy seed packets. However, its not that easy. Sky lupine seeds are tough and unpredictable to germinate. Friends have been sending me pictures from places they’ve never seen sky lupines before- the seeds have been in the soil for decades waiting for the right year to germinate! Check out the seeds, sometime- they are beautifully marked with a shiny, waxy seed coat. The seeds are hard as rocks, meant to last years in the soil.

There are many different types of sky lupine, each adapted to its own microclimate. So, if you really really want to get some sky lupines growing, get to a patch nearby and get local seed- collect the pods as they start to dry. Place the drying pods in a paper bag in the sun and wait. Soon, you’ll get to hear the pods exploding in the bag and you’ll know that you got some good seed. Make sure that the pods and seeds are nice and dry before storing them until next fall. As the first rain storm is predicted, cast the seeds around where you want sky lupine…rake them into the soil if you can…and wait- sometimes for years!

Lupine Places

Back in the early 1900’s, many regular Santa Cruz citizens would enjoy Spring wildflower trips to the North Coast grasslands to collect wildflowers. They would bring bouquets home with them and garland their hair and clothes with colorful displays. Now, with long mismanagement of many of those grasslands, there are few wildflower patches left. Anyway, if you do find wildflowers, you’re not supposed to pick them anymore. We ought to leave them for whatever remnant populations of rare pollinators might be around, waiting for us to figure out how to better manage the prairies.

Locally, two places to visit sky lupines come to mind. It used to be that the Glenwood Preserve in Scotts Valley had good sky lupine displays, but I haven’t had a report this year. A little drive to the south, and spring always brings great sky lupine displays in the grasslands and oak savannas of Fort Ord National Monument. There’s something particularly appealing to me about the large patches of sandy grasslands full of lupines surrounded by gnarly short coast live oaks at Ft. Ord. Those sky lupine patches are frequently large enough to get that lupine smell, experience that upside down world with the sky on the ground, and thousands of bumble bees bopping around the flowers.

-I originally published this post at Bruce Bratton’s weekly blog BrattonOnline.com