Imagine you are a mountain lion, a badger, or a burrowing owl making your way around our region. Curiously, people often say, ‘I can’t imagine,’ but I contend that our imaginations are more powerful than that. We can imagine a lot if we have enough information to work with and give our minds the room to roam. We can put ourselves in the place of other species if we want, but only if we can face the pain that such empathetic contemplation may bring. We have left wildlife so little, but we have the power to restore healthy populations of wildlife for future generations.

Big Clever Cats

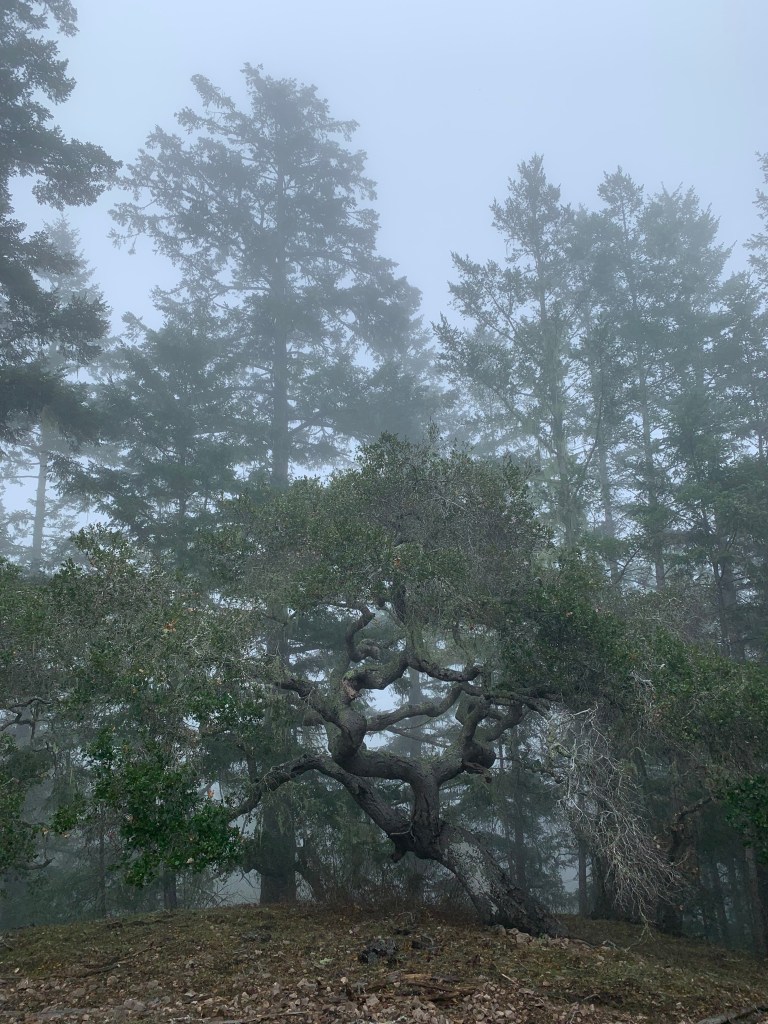

We have the great fortune to share this landscape with wild lions. To put yourself in the lion’s mind, imagine being a young male learning to walk from Aptos to Scotts Valley, getting across roads, keeping away from people, trying not to make their dogs bark, and staying under constant cover of forest. That young lion will also be learning, by scent, where girl lions are and where other murderous males have claimed territory.

Cat Map

Lions know how large to guard territories against one another to keep sufficient food for their families. Fresh deer are needed, one a week for each mature lion. A human hunter would be challenged to keep that pace up; it takes a lot of roaming. Mountain lions move under cover of trees, they shy away from moving around in the open if they can help it. They travel tree filled canyons, wooded ridges, and trails through the forests. To them, those places are like our road network- they must make mental maps as quickly as their young minds can do it, and those maps must keep receiving layer after layer of new information – especially where other lions prowl.

Badger

Two weeks ago, I was very pleased to find many badger-dug burrows in grasslands along the North Coast. Badgers look at the landscape in the opposite way that a mountain lion might. Where lions see woodlands as their comfy place, badgers prefer grasslands – maybe in part because of the lions in the forests! To imagine moving around the landscape like a badger, think about walking from the grasslands above Watsonville to the grasslands along the North Coast by staying mainly in grasslands, each night digging a burrow to sleep in, finding enough gophers and ground squirrels to eat along the way, getting across roads and never being seen by a human. That’s some tough going!

Burrowing Badgers

The burrows I saw were not fresh, and I couldn’t find a den. The badger foot tracks had been washed entirely away by a prior pouring rain. Probably this was a wandering individual, who kept moving after staying for a few weeks. Males disperse widely – even through forests. Someone was surprised to see a photo of a badger on their wildlife camera in a north coast redwood forest a few years back. I haven’t heard of anyone finding a badger burrow in a forested area.

Like vampires, badgers must be underground by daylight. Digging burrows is best done in sandy soil. And so, badgers’ mental maps include not only the network of grasslands, but also the subset of grasslands with homey sandy places where they can easily dig for food or make burrows.

Santa Cruz Badgers: Gone

There used to be badgers near Santa Cruz, not that long ago. They still occasionally happen through. When UCSC’s Chris Lay compiled local badger sightings and analyzed this species’ local disappearance, he concluded that roads explained badger demise. Roads are a big challenge to badgers. The frequent median barriers popping up on local highways have been important in saving human lives, but to badgers they are sure death. Conservationists in Great Britain, where badgers are held in perhaps higher esteem than here, have gone to great lengths to make sure badgers are now able to cross highways – laying down fences to guide badgers to the safety of underpasses.

Burrowing Owls

Burrowing owls probably see the landscape much like badgers- their homes are also in grasslands. Unlike badgers, though, burrowing owls navigate landscapes on the wing, so maybe roads aren’t so lethal. These wide-eyed, cute, bobbing, yellow-legged owls also used to frequent the meadows near Santa Cruz, but the last nesting colony was paved over by the administrators of UCSC. Now, burrowing owls are wintertime visitors only, travelling from their summer nests in inland grasslands. I wonder if burrowing owl families that once nested along the coast remember their coastal habitats and have been leading one another back to the warmer coastal grasslands each year?

Owl Trip

To imagine a burrowing owl flight to the coast, you’d be starting probably in the grasslands east of San Jose. As the nights get chillier and shorter, something in your burrowing owl mind makes you want to fly towards the coast. One long flight across the buzzing Silicon Valley city scape blanketed by nasty air pollution and you might land in one of the few remaining grasslands on the east side of the Santa Cruz Mountains…. or you might keep flying all the way to the coast. This flight would be different than most of your flights all summer long, which have been much shorter. While you are taking this long flight, you keep alert to the increasing threat of peregrine falcons…listening for the alarm calls of other birds. As you get towards the coast, you feel anxiety as each year the available habitat has been reducing: will you find a place with good cover for the winter?

Coastal Burrows

A month or so ago, I went to UCSC’s East Meadow to see burrowing owls but couldn’t find any sign of them. I looked for the owl’s wintertime homes, but they were gone: the many ground squirrel burrows in the East Meadow are gone and I couldn’t find any. In fact, there were no ground squirrels AT ALL! Anyone know what happened to them? Please let me know if you do. Long ago, UCSC administrators destroyed the last burrowing owl nesting area in the County, and more recently they destroyed the burrowing owl wintertime burrows at Terrace Point, so I’m suspicious about this new loss. Now, the UCSC wintering owls must join their friends to hide in culverts or pipes along the North Coast for their winter homes.

Linkages

“Progressive” Santa Cruz is working on its first project expressly acknowledging the need for wildlife movement across this landscape, but much more is needed, and we can all help. Informed by much science, the Land Trust of Santa Cruz County is working on creating a wildlife tunnel near Laurel Curve on Highway 17. To work, the land on either side of the tunnel must also be wildlife friendly. This corridor is in a wooded area and designed especially for mountain lion movement…maybe badgers can find it, too! Further South and East, groups are making great progress at protecting the wildlife movement corridor between the Mount Hamilton Range and the Santa Cruz Mountains through the Coyote Valley. This corridor relies on existing bridges under Highway 101 and also envisions some improved crossings over the Monterey Highway, which has median divider in many places. Badgers need this corridor to get to our region, but many other wildlife species could use this corridor- maybe even tule elk! These efforts need our financial support. We can also help wildlife movement by supporting better planning for protected wildlands, such as opposing the Homeless Garden Project’s newly hatched plan to move into the Upper Main Meadow of the Pogonip…or the seemingly continuous push to increase the numbers of trails crisscrossing parks. I hope you will take some time to imagine how your favorite species of wildlife travels across what’s left of this highly fragmented landscape… and how you can help restore the landscape we all need.

This essay reprinted from the one I original published via Bruce Bratton at BrattonOnline.com