Shall we all agree? Injustice shall not stand! But what are the ultimate measures of environmental injustice, and how do we make those responsible for violating those measures more accountable? Shouldn’t these be the primary questions we pose as ethical humans concerned with the welfare of future generations? As the which came first the chicken-or-the-egg statement goes, ‘no peace, no justice.’

Species Loss and Soil Loss

I posit that the loss of species is the primary measure of environmental injustice. And I would suggest that soil loss is, as a measure, just as important. It is sometimes difficult to make the case that a given species is critical to the welfare of humans. But any informed, rational conversation on the subject will eventually conclude that the most justice is served by ensuring all species survive. It is similarly difficult for most people to understand and discuss the importance of keeping soil in its rightful place. And again, if people take the time to have informed rational discussions on this matter, they will conclude that is absolutely critical that humans do everything in their power to ensure that soil is not lost…from any place.

Measuring Success

Humans have become expert at measuring things, and there are easily available metrics for monitoring species and soil health. The federal government of the United States has an Endangered Species Act and a Marine Mammal Protection Act and the State of California has its analogues. These two very powerful pieces of legislation demand a science-based approach of measuring the degree to which species are approaching extinction, publishing lists of species which have entered that trajectory, and demanding humans take the actions necessary to recover those species back to healthy populations. With those rules, we have progressed well in our species health measurements, database management, analyses, and predictions – oodles of very smart humans’ careers are spent on these issues. The US Fish and Wildlife Service, National Marine Fisheries and California Department of Fish and Wildlife are the authorities responsible for protecting species.

Similarly, both the federal government and the State of California have strong legislation to address soil loss. The federal Clean Water Act and the state Porter-Cologne Act both address soil loss where it can most easily be shown to affect human welfare: in wetlands, streams, and rivers. Again, humans have become adept at measuring soil (aka ‘sediment’) levels in our wetlands and waterways. The acting authority for both pieces of legislation is the State Water Quality Control Board, acting with Regional Water Quality Control Boards…ours being the Central Coast office based in San Luis Obispo.

Progress?

We have had some success, but mostly we are failing to address species decline and soil loss. The Monterey Bay region has excellent examples of both the limited successes and abject failures with both issues. If you get to Moss Landing or Monterey and hop on a whale watching boat (and I hope you do!), you can predictably view endangered species that, due to legal protections, measurements, and adaptive management, have recovered somewhat from extinction. Hike at the Pinnacles, and you can see California condors which most people feared would go extinct not that long ago. Walk on some of our local beaches and you might see a snowy plover…another species who owes its survival around here to the Endangered Species Act. Same with the southern sea otter, marbled murrelet, and the central coast populations of steelhead and coho salmon. If I’m convincing you of humans’ ability to reverse species extinction, you are being premature. All of those species, and dozens more endangered animal species remain on the federal and state lists of imperiled species because they have not been recovered. And, many, many more species qualify for listing under the state and federal endangered species acts but the authorities haven’t spent the time to analyze them. Locally, only the peregrine falcon has been ‘delisted’ – no small feat! The reason so many species are so tenuously holding onto their existence: lack of accountability.

Accountability

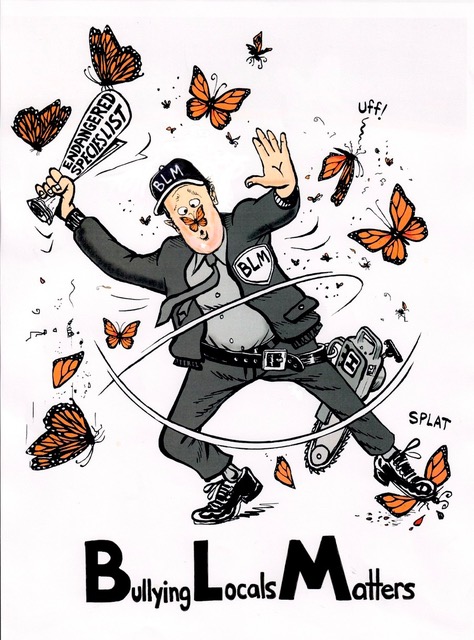

Holding people accountable begins with measuring their success. After legal action by the Center for Biological Diversity, the US Fish and Wildlife Service has been dutifully publishing 5-year reviews of the status of each federally listed species; the stories in those reports are not good, but their reports fail to go so far as to hold anyone accountable. Turning to our much-vaunted free press, The Intercept recently published an exposé that illustrates who should be held accountable for the lack of protection afforded endangered grizzly bears. That story, and similar stories I’ve documented from around the Monterey Bay, point to problems with the justice system. If you haven’t figured it out yet, the US justice system is seriously in trouble: there is no justice in the USA! As shown in that Intercept article, anyone can destroy the habitat of, or kill individuals of, any endangered species and easily get away with it.

Local Examples – Endangered Species

Whale species, snowy plovers, Ohlone tiger beetles, California red-legged frogs – all local endangered species with good documentation of legal infractions that have gone unanswered. There are films, witnesses, and reliable first-hand accounts (including by legal enforcement personnel) showing boat captains purposefully pursuing and interfering with the movement of – harassing – legally protected whales on the Monterey Bay…and these are ongoing situations. When interviewed, Federal enforcement personnel say that it is hopeless to enforce such infractions because they report to too few legal personnel and those personnel say such cases don’t stand any hope of holding up in court. Similarly, State enforcement personnel say that unless they catch, film, and have witnesses of someone in the act of killing an endangered sea otter (with ‘blood on their hands’ and a ‘body in their trunk’) there is no hope of legal enforcement of the many more frequent (and well documented) situations of human behavior negatively impacting that imperiled species. Again, they say this is due to limited legal bandwidth within their agency and the hopeless nature of the justice system in convicting anyone. In Florida, there is good legal precedent for finding parks agencies responsible for allowing visitors to trample endangered sea turtle nests. In Florida, as with California, state parks personnel are required to plan for such endangered species protection, even on popular beaches. Around the Monterey Bay, parks agencies routinely allow visitors to trample endangered snowy plover nests and squish endangered Ohlone tiger beetles: there’s documentation aplenty with both situations. As recently as this past year, park agency personnel have destroyed wetlands occupied by California red-legged frogs to ‘improve’ trails. In past years, park agencies have graded and graveled trails, destroying Ohlone tiger beetle habitat. When reports reach federal officials, they respond that they contact parks personnel, admonish them, receive apologies, and then they forget it…there is not one bit of justice served!

Local Examples – Soil Loss

I could, and will in a future essay, provide a similar litany of examples where responsible agencies have failed to enforce regulations designed to address soil loss. The San Lorenzo River is ‘listed’ as impaired by sediment- soil loss in that watershed is rampant and largely unaddressed. There is more to come on this.

Upper- and Lower-Level Accountability

What do we do? If voters don’t demand that District Attorneys enforce environmental crimes, they won’t. If we don’t demand that our politicians have environmental platforms, they won’t work to improve the justice system so that it protects species and soils. But is the fault really way up there at those ranks? Can’t we demand accountability at lower levels? After all, unless we work together at every level, we won’t succeed.

If you see something, say something. We must have compassion for the enforcement personnel who so want to do their jobs but feel disempowered. And let’s learn how to be good witnesses, how to provide the right reports, and how to help document the two primary root environmental justice issues. Evidence must mount from more people more frequently. We must also make sure that the evidence is well stewarded: I look forward to annual reports from enforcement agencies about the frequency of infractions that remain unenforced.

Finally, why do we allow parks agencies to keep operating so that visitors are destroying the endangered species that those parks were designated to protect? Why do parks personnel allow so much soil loss from roads, trails, farms, and buildings? This goes beyond enforcement. This is a political issue. No one wants such injustice.

-this essay originally posted by the wise Bruce Bratton, who aligns some of the areas’ best minds to post in his weekly blog at BrattonOnline.com – why not subscribe today?