A recent negotiated settlement at Point Reyes National Seashore is the latest example of how controversy over cattle grazing on public land gets resolved. The polarity is typical. On one ‘side’ are ranchers, their families and workers, and the broad community that supports family farms, local agriculture, and organic or nowadays regenerative agriculture. On the other ‘side’ are environmentalists, pro-species, pro-clean water, pro-wildlife, and anti-livestock where there’s profit on public lands. The battle at Point Reyes is just one in this war across the U.S. West, and it has been going on for decades. At least at Point Reyes, the two sides don’t neatly align in the expected ways between the two mainstream political parties. Why did it get so bad at Point Reyes that legal action and tens of millions of dollars were needed to settle the issues? Could this kind of thing occur on public lands closer to the Monterey Bay? Let’s look closer to see.

The Vast Gulf

Conflicts with recreation, water quality concerns, and impacts on native plant and wildlife species are the issues most commonly raised when there are concerns about cattle grazing on public land. And, there is good science to support the value of carefully planned cattle grazing to reduce wildfire impacts while promoting native plant and wildlife conservation. In addition to these types of issues, there are pro- and anti- cattle advocates out there, on one hand in support of agriculture or cute critters for children to adore; and, on the other hand, wanting only native animals on the land or against meat eating, methane producing, and otherwise cruel corporate cattle corporations.

Radical Center

There are many of us who are experiencing the beauty of collaboration between livestock managers and conservationists: we are achieving more emergent success than anyone thought possible 30 years ago. Chief among these collaborative networks’ concerns has been development and sprawl…greed that replaces private ranches with housing tracks and shopping malls. In California, we also have shared concerns about the vitality of ranching economics, water provision, wildlife conservation, and catastrophic wildfire. Each of these issues has seen progress because a respectful, trusting network keeps showing up and working together. It takes everyone who has an interest in land management to create innovative solutions: ranchers, conservationists, researchers, land managers, regulatory agencies, community members, resource advisors and consultants, and planners. But, each of these groups has unique interests, different languages, different cultures. We get past these differences by gathering together and learning from one another in well planned, moderated dialogues. The Quivira Coalition is the first group I know to start these discussions, and many followed. The Central Coast Rangeland Coalition (CCRC) is working on this stuff locally, and is celebrating its 20th Anniversary in 2025. I copy here the pledge from the Quivira Coalitions website (link above), a pledge that mirrors the work of other groups like the CCRC:

“We pledge our efforts to form the `Radical Center’ where:

- The ranching community accepts and aspires to a progressively higher standard of environmental performance;

- The environmental community resolves to work constructively with the people who occupy and use the lands it would protect;

- The personnel of federal and state land management agencies focus not on the defense of procedure but on the production of tangible results;

- The research community strives to make their work more relevant to broader constituencies;

- The land grant colleges return to their original charters, conducting and disseminating information in ways that benefit local landscapes and the communities that depend on them;

- The consumer buys food that strengthens the bond between their own health and the health of the land;

- The public recognizes and rewards those who maintain and improve the health of all land; and

- All participants learn better how to share both authority and responsibility.”

Who is Showing Up, Who is Not

Where do you see cows on public land; how is it working; how do you know? There are cattle grazing on Midpeninsula Open Space, Santa Clara Open Space, State Parks (Pacheco State Park), BLM (Ft. Ord, Cotoni Coast Dairies), POST, and on City of Santa Cruz (Moore Creek, Arana Gulch). Of these, MidPen, POST, and Santa Clara regularly show up to work with the CCRC. I believe that these are the organizations that are most apt to succeed and least likely to end up in the terrible situations that Point Reyes has been experiencing. Why do some show up and not others? I suggest that the third bullet is as important as the next-to-last. It takes the oversight agency’s interest in results as well as the public’s engagement to nudge public land managers to the table.

My Experience at Point Reyes

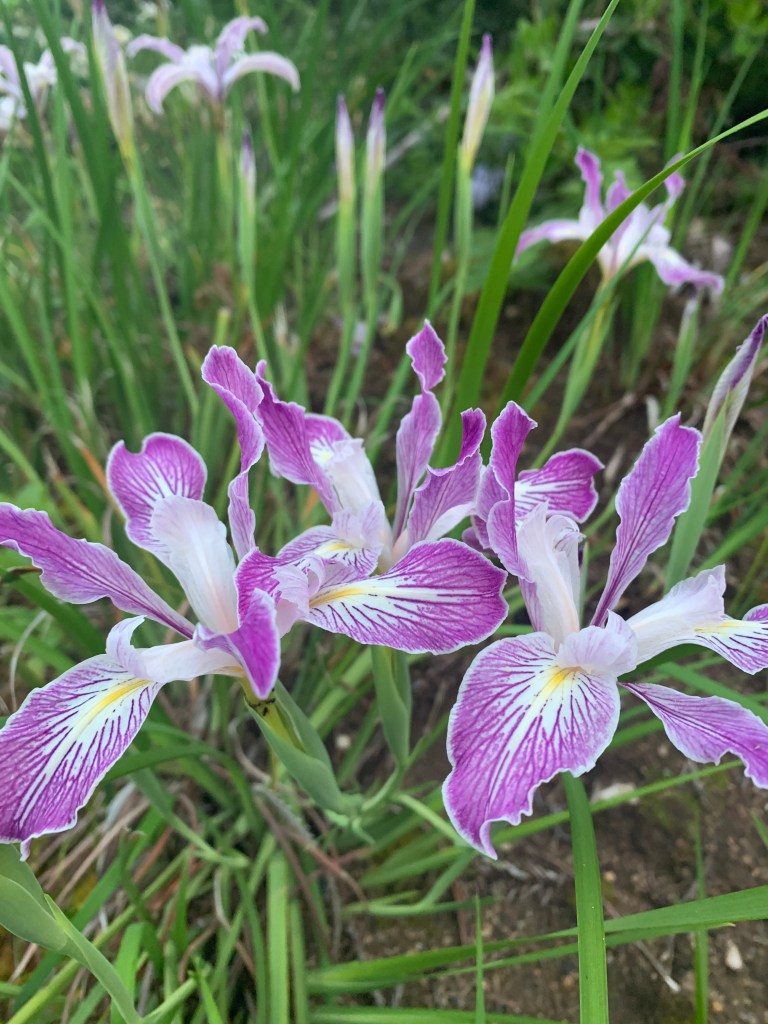

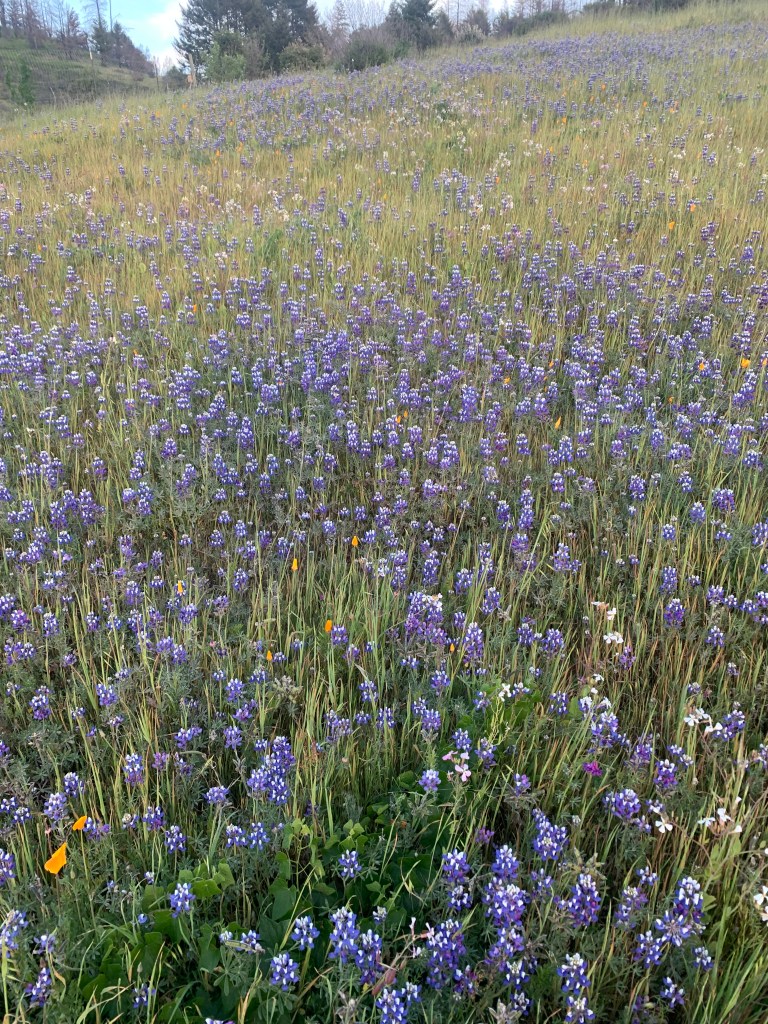

I am an unabashed native plant conservationist, have researched and visited coastal prairie habitat at Point Reyes for many years, and I have NOT been impressed. Two of the science papers that got me started on my doctoral research were from Point Reyes. One told the story of a rare wildflower that was protected to death when cattle grazing was removed from its wetland habitat. The other illustrated how another rare wildflower thrived because of an appropriate cattle grazing regime. I consequently surveyed across fencelines at Point Reyes and found native annual wildflowers to be more diverse and abundant on the cattle grazed side of the fence, as opposed to the side where grazing had been excluded. In fact, I found the very rare San Francisco Owl’s clover in abundance in the areas with, and not so much without, cattle grazing. I have subsequently made many returns to Point Reyes to learn about what is going on. During one field trip, I found out that the cattle ranchers and park managers had only the most rudimentary ability to discuss a topic that had long been a priority, common interest: the encroachment of brush onto coastal prairies. During another excursion to explore the health of the very endangered Point Reyes Horkelia, park employees indicated that not only did they not have any data to share about the health of this species, but also that I was not permitted to monitor the species without extensive paperwork, even in areas open and easily accessible to the public (see bullet point above, re: defense of procedure vs. production of results). Nevertheless, I found that the cattle grazing regime had hammered nearly to obliteration this rare species whereas adjoining cattle excluded areas still had a few individuals which were on the verge of being obliterated by weeds, especially iceplant, a species that is relatively easy to eradicate in such instances where it is a local threat to an endangered species. I’m sure that the cattle rancher had no idea about rare species and I’m sure that the Park employees had never considered talking to the rancher about its conservation. In my experience, such communication is essential to improved success.

Where From Here?

Reflecting on my experience at Point Reyes, I am unsurprised about the recent outcome, but I am undeterred to keep helping the Central Coast Rangeland Coalition avoid such unproductive mayhem wherever possible. I challenge the Bureau of Land Management, State Parks, the City of Santa Cruz, and all other land stewardship entities to take the above pledge, joining constructive dialogues that demonstrate success at taking care of our lands. And, I challenge everyone else who is reading this to take the portion of the pledge that applies to you. I especially challenge the “Conservation Architects” (you know who you are)…including those who think highly of the concept of a “Great Park” designed to encompass most of the Santa Cruz Mountains…to now doubly consider what kind of baby-sitting federal agencies need to achieve conservation success. Together, we can make a difference. But, we need the principles of Radical Center-based collaboration (as articulated above) to take root in all places before we will see the harvests we so desperately need.

-this article originally published as part of the ongoing BrattonOnline news service, covering the Monterey Bay and Beyond. Subscribe and win!