Of all the phenomenon of Fall, seeds rein. Just as humans become silent around the table as they dig in, mouths full of the bounty, so have the non-human animals across the fields and forests surrounding Molino Creek Farm. A pale blue scrub jay appears on a high perch, its beak pried wide, holding a huge acorn. It dives to a patch of grass, furtively glancing about to assure no one is watching, and buries the acorn, no pause and it’s off for the next. Our normally squawky friends are quite busy with their oak harvest, back and forth, planting hundreds each day. It is not a great acorn crop year, so the competition is high.

The tiny goldfinches disperse like confetti in small flocks, alighting in field margins or scrubby areas to harvest the oil-rich seeds of thistles, prickly lettuce, and tarplants. Their songs, too, are muted, chatter replaced by dainty beak-seed-cracking.

Redwoods

Fall in the wooded canyon means redwoods shedding needle-branches and a rain of seeds from newly opened, small cones. Recent gusts broke loose short sections of the outermost branches from redwood trees. Thin-stemmed branch tips are mostly needles, which are regularly shed this time of year and carpet trails and roads. Even ‘evergreen’ trees shed needles at regular intervals, each species with its own season. And so, the forest floor transforms from last year’s now dark duff to a light, red-brown coating of fresh redwood litter. Walking our Molino Creek Canyon trail now creates a crunchy, crackly sound. On a recent walk, I glanced down to appreciate the redwood fall and saw many redwood seeds sprinkled between the scattered needle branches. A heavy breeze swayed the trees back and forth over me and in all directions, and the air was suddenly filled with redwood seeds, bigger than dust and thickly moving like sheets of drizzle.

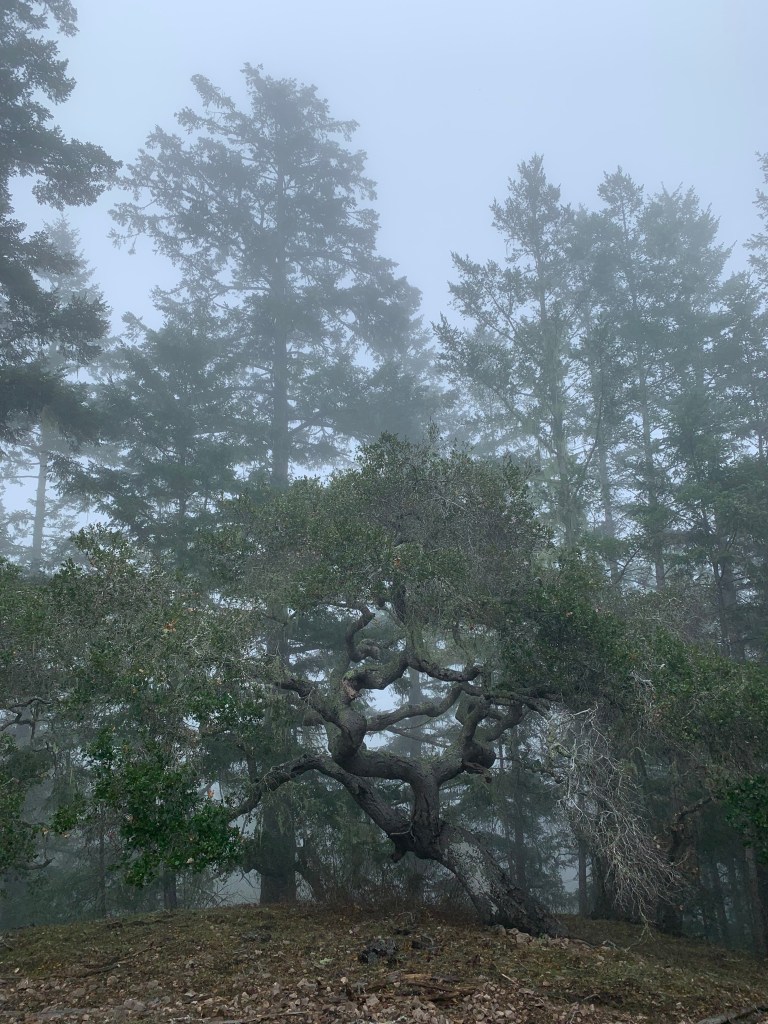

Madrone

A beautiful element of our woodlands is the flesh-smooth orange-barked madrone, becoming bedecked with ripening fruit, held high in the canopies. Presented in diffuse clusters just above their large oval shiny dark green leaves, the ripening madrone berries are changing from hard and green to fleshy and bright orange-red. Band tailed pigeons and other birds are feasting, sometimes knocking the ripe fruit to the ground where mammals gobble them up. When I am lucky enough to find a grounded, deeper red fruit, I also pop it in my mouth, reveling in the sweetness, near strawberry flavor.

Walnut

The prominent black walnuts, the signature trees of the farm, are turning lemon yellow and dropping ripe nuts with a plunking noise to the ground. The 2” fleshy globes roll about a bit after dropping from the trees, settling in the grass or, more evidently, on road surfaces. The sound of tires used to be the scritch of gravel but is now accentuated with the resonance of the rubber drum when a run-over tough walnut pops and gets crushed into the road. Ravens and juncos line the roadside fence awaiting the freshly exposed juicy, oily, tasty nutmeat that is announced by the tire drum “poing.”

Pome Pome, Pome-Pome!

The fruit that we eat (and drink) is rolling off the trees in delicious piles and buckets and boxes and carts. We are more than 2,000 pounds into the 4,000 pound harvest, down from last year. Nothing goes to waste. There are very rare instances when someone doesn’t pick up a really gooey apple from the orchard floor. Hygiene is in high swing with the worst orchard trash heading to the weed suppression wildlife feast buffet. The deer, rabbits, quail and coyotes take turns at the castings: nothing lasts more than a few days. The last tractor bucket of culled apples, 200+ pounds, was mopped up in 2 days, down to bare earth.

That leaves 3 other types of apples: sale apples, take home apples, and cider apples. The most common harvester and sorter vocalization is ‘awww!’ as they realize the rarity of the perfect fruit, the choice apple that is sent to market. That’s one in 8 this year, due to the uncontrolled apple scab of the moist spring. The other 8 apples are 30:70 take home apples versus cider apples. The take home apples are sent in boxes, buckets, and bags to the growingly extensive community orchardists; they have the most minor blemishes and there are hundreds of them. Our working bee network has been making their own juice, drying them, stewing apple (-quince) sauce, and just plain enjoying the crisp diversity of flavors from the many varieties we grow. The cider apples have a few more blemishes or even some signs of worms…the latter making work for the cider pressing party as chattering, smiling clean up crews prepare the fruit for a better juicing.

Juice!

The cider pressing last Saturday attracted 30 or so of our network, new and old pressers, taking the 500 pounds (or more) to 30 (or more) gallons of nectar – delicious juice. Much of this will become hard cider for future gatherings; many enjoyed diverse ciders from prior pressings. Most abundant fruit of this year’s press, Fuji, but also Mutsu which makes famously fine flavored juice. Mixed in here and there were true cider apples, varieties that are just starting to produce after 8 years in the ground. The cider apples add bitterness or sourness or tartness and overall complexity to the juice from what would otherwise be plainer if produced only from table apples.

The Community Orchardists sponsored a recent squeezing of fresh juice for the Pacific School in Davenport, our neighborhood! Bob Brunie schlogged the equipment and demonstrated the process to the schoolkids, some of whom were returnees and they enjoyed it a whole lot..

The falls’ fruit produces juice, brewed into all seasons’ mirth. With toiling gladness, we renew the stocks annually. Cycles of production and consumption – foundational in nature – quench more than mere bodily thirst, leading to deeper appreciation of Earth.

-this post also shared via Molino Creek Farm’s website, same time, same author