The Peninsula Open Space Trust (POST) recently published an article about a 2023 regional trail user survey. The author of the article, Zionne Fox, wrote about some of the results of the study, and her writing helps gain new insights into POST’s philosophy regarding recreational use in natural areas.

Summary of the Article

Ms. Fox’s “blog,” published on August 28, 2025, announced the findings of a ‘unique’ regional study by the Santa Cruz Mountains Stewardship Network that had purported to assess parks trail user expectations. Fox reports the percentages of different user groups (equestrians, dog walkers, hikers, mountain bikers) that want more trails. She also notes that non-white respondents were statistically under represented. The article suggests (without supporting data) that demand for trails is growing and that ‘open space operators need practices that can meet rising visitor expectations while preserving natural habitat.’ There was also mention about many equestrians hailing from Santa Cruz County and (again, unsubstantiated) a need for additional accommodation for multi-day trail trips.

Reporting Issues

The POST article fails in many ways to meet the standards of responsible reporting, but that is predictable given the organization’s overall tendencies. First, note that the study referenced isn’t, as the author claims, ‘unique,’ at all: another, more professional study covering much the same material was published not that long ago. Also, notice that there is no link in the article to a report about the results of the survey. With further research I find that the survey authors, the Santa Cruz Mountains Stewardship Network, lacks a link to any reporting on the survey results on its website. Without more details about survey methodology, statistical analysis, and results it is difficult to draw one’s own conclusions.

Moreover, the article emphasizes only the survey results which correlate most with POST’s own goal of increased recreational use of ‘open space’ lands. For instance, statistics are provided for apparent unmet needs from various recreational groups, but similar statistics are not presented about the degree of concern for natural resource conservation, which is at odds with increased recreational use. In fact, in the ‘What’s Next’ portion of the article, there is no mention of POST’s or any other ‘open space operator’s’ intention to address survey respondents’ concerns about conserving and nurturing natural resources which suffer from over visitation. Similarly, POST suggests that those operators should focus on ‘preserving natural habitat,’ which curiously avoids the more concrete and pressing issue of conserving the specific species that are sensitive to natural areas recreational use. Habitat preservation is nearly meaningless to measure, whereas species conservation is much more useful and quantifiable, with a richer history of scientific rigor in informing open space management.

Note that the author of this article fails to mention any results from the portion of the survey asking about trail user’s negative experiences in open space areas. The survey asked poignant questions about negative interactions with dogs, people biking, shared trail use with other users, etc. Such conflicts are expected and are a challenge that trained park managers are used to addressing; unfortunately POST lacks staff with such expertise, so it is understandable that the author would avoid mention of this portion of the survey, which would otherwise reflect poorly on her organization.

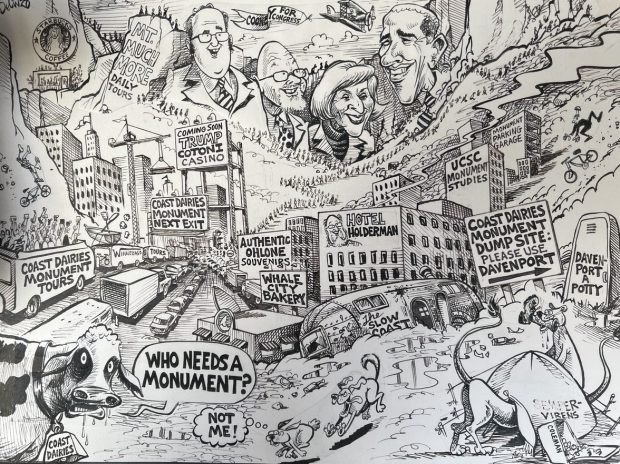

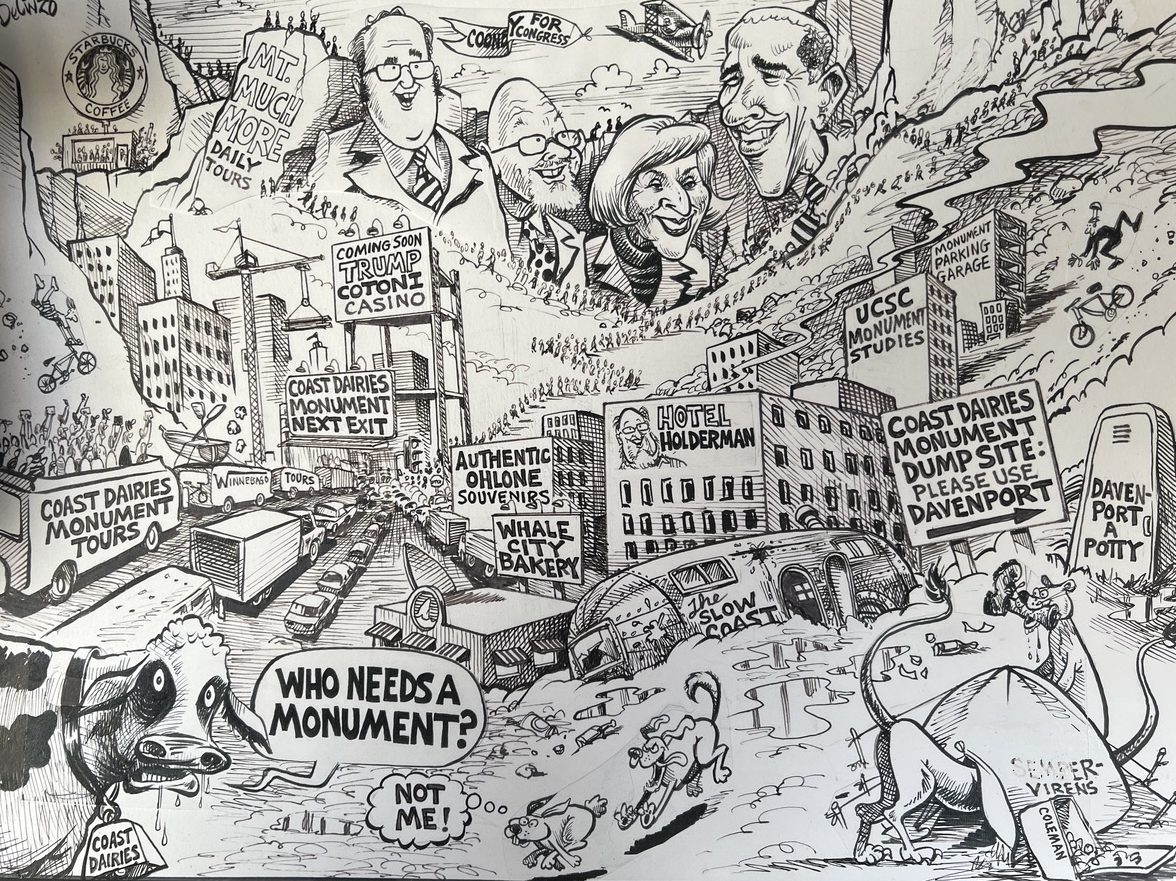

The reporting insufficiencies and biases should not be surprising to those who follow POST. This is an organization focused on increased recreational use at the expense of species conservation. For instance, while on one hand cheerleading for the National Monument designation of Cotoni Coast Dairies, POST refused to sign onto a letter advocating that the designation include specific protections for natural resources. Peruse the organization’s website and you’ll find that species conservation is de-emphasized as opposed to an over-emphasis of recreational use of natural areas, which negatively affects nature. While being the best funded private organization working on open space issues in the Bay Area, POST has apparently never hired staff or engaged contractors that are professionals at managing visitor use in such a way that demonstrably protects the very species that require POST’s natural areas to survive. POST has published no reports or plans to address these concerns, at least none that are available to the public.

Methodological Issues

On its face value, the survey issued by the Santa Cruz Mountains Stewardship Network lacked the rigor to make the kinds of conclusions that POST suggests would be valuable. As opposed to previous, more rigorous studies the survey failed to sample the breadth of the population with interests in open space areas. POST notes that proportions of respondent self-reported ‘race’ did not reflect the population as a whole, but failed to note how the survey may have also biased certain user groups over others (mountain bikers vs. hikers, etc).

One would expect to encounter survey bias given the mode of delivery. The survey was a web-based survey distributed by social media networks. Open space organizations have recently become increasingly aligned with a vocal minority: well-funded mountain biking advocacy groups who undoubtedly circulated the survey in order to impact the results. Other trail user groups may have been under-represented because they have little exposure to those particular social media networks or because they lacked the computer technology to respond.

Cautionary Conclusions

We can learn valuable lessons from POST’s reporting on this trail user survey. Given the power of POST, we should continue to be vigilant about the group’s propensity to favor increased recreational use of open space lands at the cost of species conservation. This bias should make us question the organization’s ability to manage funding tied to protection of public trust resources. POST is a donor-funded organization, and so some degree of pressure from donors could help to steer the organization more towards conservation. We should also recognize that POST is not alone in making these types of mistakes. It appears that the Santa Cruz Mountains Stewardship Network is also allied with such thinking, and we have seen other conservation lands managers approaching open space management with similarly unbalanced methodologies. These trends must be reversed if we are to conserve the many species of wildlife which are sensitive to poorly managed recreational use in our parks.

As time passes and we stay alert to the possibilities, we will see if the poorly executed SCMSN trails user survey results are used to justify or rationalize actions by POST or other members in their network: wouldn’t it be a shame if they were?

-this post originally published in my column for BrattonOnline.com – a weekly blog with movie reviews and posts by very interesting people on matters near and far. I recommend subscribing to it and donating so we can continue this long tradition.