– this is the last of my regular posts from the Molino Creek Farm blog for 2021, stay tuned for more regular posts February 2022.

For now, I put down my farm tools and stow them oiled and sharp, ready for next Spring. In the orchard, we coil hoses, hang irrigation pipes among the branches high off the ground so they don’t get buried and inadvertently mowed. We cut free and pile remaining tree props and haul and spread the last of the chipped oak branch mulch.

Apple leaves slowly fall, holding on long with fading yellow beauty. The last of fall’s leaves won’t drop until January, the fruit trees revel in the cool moisture after being blown by dry air during the long summer. But the fading light of shortening days push the orchard trees into their necessary and healthy sleep. Even we feel this pull.

Togetherness

The long cool still nights descend rapidly, driving us indoors early to stoke woodstoves and await the roaring warmth. We shed clothes and gaze at firelight, relaxing into the many-hour evenings. It is time to gather sometimes with family, sometimes with friends. Some find these gatherings especially precious from a year spent in solitude and self-reflection. Sparkling eyes greet us, loving words spoken close to our ears during long greeting hugs. Some are no longer with us or will soon be gone. We feel the losses more keenly during the gatherings, close to the warmth of others…spontaneous hushed moments we dare not fill.

Whence the Feasts?

Sighing, we raise from our chairs and head for the kitchen, for this is a season of feasts. The food is from farms. Somewhere in our minds, we hope at least some of our grocery purchases support family farms…maybe that farmer’s market trip helped keep family farming alive. Sometimes it does!

Some say we need to be thinking about new farming models, cooperatives combined with higher wages and increasing food costs, where broader support helps free farming families from the 80-hour weeks that’s required to pay the bills, to raise and support children. For cooperatives to work, we need to find a way to get along, to work together, and we also need for people to be willing to pay more for food. We desperately need more young farmers.

As we eat our food, as we chew, imagine the people it took, the many jobs and steps it took to bring that food to your mouth. Picture the water…the rich soil…the sun that helped produce your food and the tender hearts of (aging) farmers who smile proudly as they reflect on each stage of growing their crops. The newly tilled field, and the sowing. The seedlings planted…eventually the first flowers, then the tiny new fruit. There’s also the watering, the pest control, the nurturing propping and pruning, and, eventually, the harvest. Right livelihood. Good food. Favorite recipes. Big feasts.

In Between, Walks

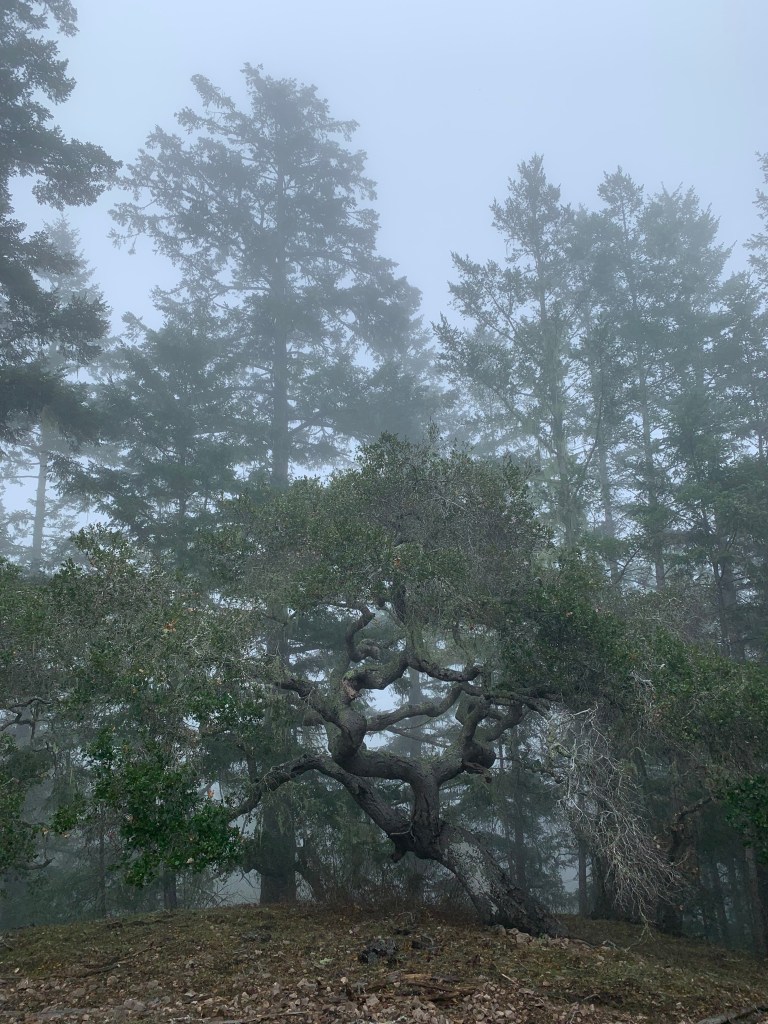

Those who are able, take walks between meals, enjoying the squinty-bright sun and catching the remaining fall color. Poison oak leaves still dot the hillsides with red, and a few maple leaves remain yellow on the ground. Across much of the wildland, there are no flowers- except in the chaparral, where the manzanitas have just the past few days burst with clusters of bloom. Hummingbirds move upslope to the manzanita patches, or feed on landscape plants; they are also spending lots of time eating bugs. Step carefully on your forest walks…there are slow moving newts moving around!

Wild Brethren

Like us, nonhuman animals are also resting between feasts. This is the break they get between periods of raising the young. I heard the peeping of a young begging towhee, the only young bird sound for the last month. The wild farm birds are the most frightened I’ve ever seen them because we have two Norther Harriers patrolling every hour of each day. When that pair are farther away, out come hundreds of sparrows, juncos, and goldfinches furtively feeding on whatever they can peck. Then, alarm calls and swooshes, they dive into the bushes to avoid the bird-killing Harriers, one right after the other. Silence. Long silence, watchful eyes, and then tentative peeps and the brave ones creep from cover to feed once again, the more cautious ones eventually following.

Nonhumans Alike

Like us, these critters are gathering and holding together with friends and family, loving each other. All day, they watch out for one another…peeping, chipping and singing their language of safety, satisfaction or danger. They go to roost early, an hour before sunset, settling into the thick cover of oak or shrub canopies for these long winter nights. There, with the quietist whispers they tell their stories, sharing their experiences after they sidle up snuggly and cozy to keep each other warm. Like us, they remember the voices of those lost, the uniqueness of the personalities snuffed by fate, taken by the Harrier or by sickness, or by old age.

Last night, two sister quails fussed about not having quite enough space on the most comfortable branch near the top of the thick canopy of an incense cedar. They chucked and chucked, whirring their wings against one another and into the surround branches, trying to make more room before eventually scrunching in and settling down. Tonight, there is more space on that, the best of the high branches, and a bobcat is curled in deep sleep with a full belly…a pile of feathers will take a while to melt into the grass and decay. The remaining sister misses her warmth and her stories but now turns to another of her kin for such comfort…listening closely to the familiar tone and pace of their murmurs, sharing meandering feelings at the end of their day, until the last low chatter brings sleep to the covey and the silence of the night settles under the dark and twinkling sky.