Compassion for others in a political setting is a challenge that, as citizens, we must all ponder. As citizens in a democracy, we are active participants in the global experiment on Nature and how future generations will fare based on our individual decisions in the moment. We purchase things, we vote, and we make thousands of choices that each has an impact on other species. Each of us has our way and our reasons. A compassionate approach to others may open the many stuck doors to create a more lasting environmental conservation movement. And, we must ponder how institutions and individuals interact to enact that compassion.

The Government

Our style of democratic government reflects the will of the Nation’s people, over time. We vote directly for one of the three branches of government – the Legislative branch – and the House directly reflects representation of the majority of the population. The Senate changes the ‘majority rules’ notion to evenness of geographic representation, no matter the population, giving small numbers in sparsely populated geographies more power. Election of the Executive branch has a system of election using delegates, which also reflects an intention to create more even geographic distribution of power, but also has aspects that embed extra-democratic power relationships including freedom of delegate choice into the equation. Judicial branch members are appointed by that Executive branch and seated when confirmed by the Senate and so also reflect the problems associated with the elections of those two portions of the government.

In short, we have a system of government designed to amalgamate the geographies, popular opinions, and existing power relations in order to make choices that we are meant to respect as ‘representative.’ The way this works is particularly challenging to issues that do not raise to prominence for voters. When votes matter, politicians and the power network that supports them sway government actions. Environmental conservation is one of those issues that the power structure never wants to see come to the fore, and citizens are easily swayed in other directions. News media and social media, which are easily manipulated, herd citizens towards issues that are both divisive and convenient for those in power. Environmental conservation threatens all members of those in power, no matter what the political persuasion.

The top issues that sway US citizens’ votes are the ones that the media focus on: the economy (always first), healthcare, and safety – e.g., police (local), military (global). Environmental concerns always rank Way Down the list, despite being the single greatest element to having a sustainable economy, healthy humans, and a safe society.

When considering environmental conservation, it is the will of those in power and the government they manifest that creates the challenges to having compassion on two factions of our society: your fellow citizen, who is in some way responsible for the government, and the employees of government institutions, who act within governmental decision frameworks.

The Citizen

How do we approach compassion, to see the humanity in our fellow citizens when the government does so little for environmental conservation? It is easy to blame governmental actions on the citizens of the country, but is it fair?

It is also easy to understand why your neighbors, friends, and relatives do not prioritize environmental conservation with their actions. We are creatures of habit living in a difficult world. It is difficult to change our behaviors, even if they negatively affect the environment. It is difficult to see our individual choices as mattering and easier to blame the impacts on the environment on other people, other nations, or even evolution, fate, or a Deity. We all do these things. When we listen to the news or tune into social media, the messages there do not help us to understand elements of environmental conservation and what we can do about them. Even the supposed ‘neutral’ (really ‘centrist’) NPR rarely covers much of the breadth of environmental conservation import and then mostly with disempowering messages. Because the US has become so expensive and the pace so breakneck, citizens are afforded almost no leisure time to learn about environmental issues. And, with the decline in broad, critical thinking education, environmental conservation has become a tiny part of anything students are exposed to, favored by Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (STEM) focus. The term ‘Science’ in STEM doesn’t mean organismal biology nor does it include any conservation elements. Highlighting this STEM education is a real success of the power structure in the US as they hope to create a (somewhat) skilled workforce.

In sum, citizens do not know, and cannot find a way to know, about environmental conservation and without such knowledge they act innocently and ignorantly in ways that collectively negatively impact the environment. Aren’t we all like that? Let’s have a little compassion for everyone and figure out where to go from there.

The Government Worker

Government workers are citizens who have even more burdens on their environmental conservation actions. Those people who work for governmental institutions that are supposed to protect the environment face all the challenges of the average citizen described above. While it is true that the government requires some of those workers to have higher levels of education to qualify for their jobs, the required bachelor’s or master’s degrees never train them for the environmental conservation elements of their jobs. The most relevant field is called ‘conservation biology.’ There are very few institutions of higher education that offer this focus, and the combined top ten programs in the US graduate fewer than 100 undergraduates, and far fewer graduate students, each year. Once out of school, these individuals have a high incentive to work in a lucrative field, environmental consulting where they can earn 5 times more than a government employee. And so, government institution personnel that are responsible for environmental conservation have not received the education they need for their jobs, have not been raised in a culture that supports inquiry, and are strained by economic and social situations that make it difficult to prioritize environmental conservation. And then they go to work in institutions with similar individuals under conditions of extreme political pressure exerted in contravention to environmental conservation.

Governmental Institutions

The government institutions that have responsibility for environmental conservation have never been designed to be effective with that responsibility. Because conservation rarely and briefly rises to the fore for politicians, consistent oversight and policy development is lacking. Instead, environmental conservation frameworks are weak and up to the interpretation of the agency. Locally, State Parks is required to have General Plans for all of their lands, but there is no required timeline for creating them, no mandate to update them (ever), and little guidance on key features of those plans such as what a ‘carrying capacity’ analysis might be. Locally, County and City Parks have no guidance at all about environmental conservation and there is none in the making. Locally, the Bureau of Land Management has guidance documents for environmental conservation, again with no timelines for enacting them and insufficient guidance to maintain the scientific integrity of those efforts.

Workers are Human, Too!

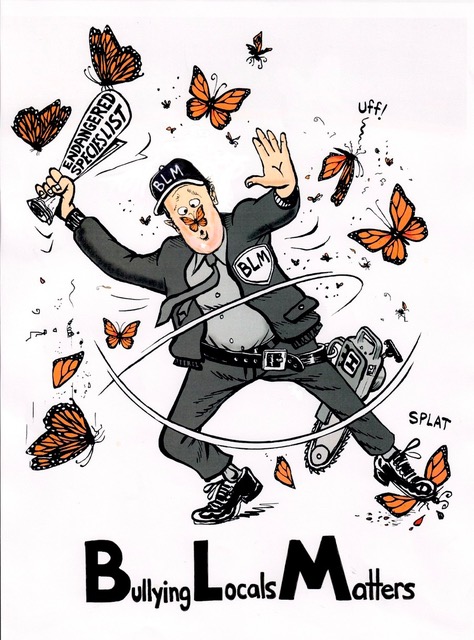

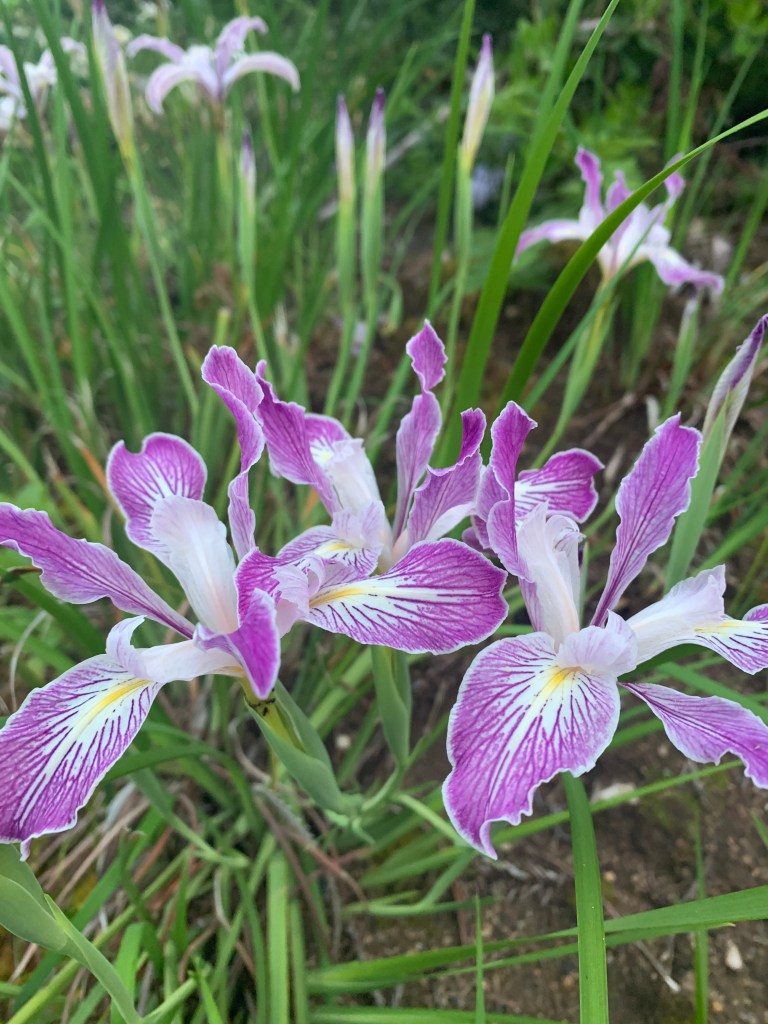

Even if they don’t recognize it and can’t hear it, the too few employees charged with environmental conservation at governmental institutions find themselves without sufficient means and support for substantive, science-based environmental conservation action. And so, they go about their jobs doing what little they can to try to make a difference. Most of them are proud of their accomplishments. Being social humans, they form bonds with their workmates and take their personal pride and form institutional pride. They are proud of the work of State Parks, they are proud of City and County Parks Department accomplishments, and they are proud to be part of the BLM team.

Many of us can relate. Many people find themselves in institutions that have elements of good and elements of bad (which sometimes we don’t want to see!); we choose to focus on the good work we are doing within those institutions. We make friendships at work and want to support those friends. Some of us work for institutions where the public believes that our work is good and just, and so it is easy to become proud of our institution and even to defend our institution when challenged. Let’s have a little compassion for the people we see who have ended up like that and figure out where to go from there so that there is better environmental conservation even by governmental institutions.

This post originally appeared in the important blog published by Bruce Bratton at BrattonOnline.com Subscribe Today!